Read time ca. 4 minutes

There have been a lot of complex negotiations, cultural tensions, and political maneuvering that marked the history of California’s statehood and shaped the US state into the one we know today. Maybe one of the most significant moments in the long statehood process was the drafting of the 1859 Pico Act, which was a proposal that reflected the great challenges that were seen while governing such a vast and diverse territory. Even though the US had already made California in 1850 as the 31st state, the Pico Act was presented as an attempt to reshape how it was governed, and it additionally addressed the frustrations of those who were living far from the political center from which they were governed. Understanding this act provides insight into the struggles of early Californians and the competing interests that shaped the state’s identity.

Background of the Proposal:

California’s admission to the Union in 1850 came at a time of rapid change. The Gold Rush had drawn thousands of newcomers, and the population grew unevenly across the state. As the political representatives were concentrated mainly in the north, especially around the cities of San Francisco and Sacramento, the communities in the southern region felt marginalized. Travel between the north and the south was difficult, with poor infrastructure and long distances adding to the sense of separation.

These circumstances gave rise to a movement in Southern California that sought either stronger local authority or separation into a distinct entity. The leader behind this effort was Andrés Pico, a Californio politician and military figure who had previously fought during the Mexican-American War. His vision was to give Southern California a government better suited to its needs, one that was not overshadowed by the economic and political dominance of the north.

The Content of the Act:

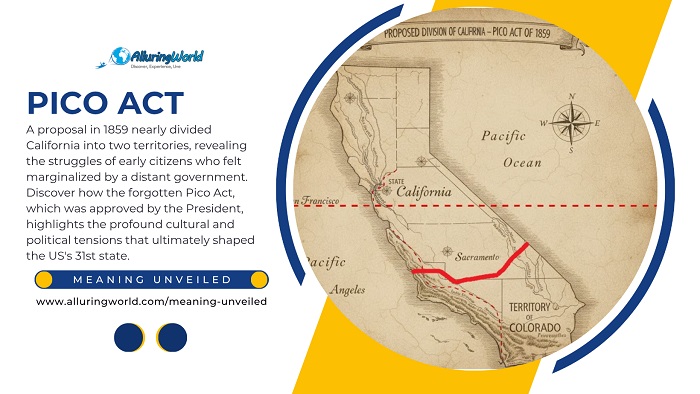

Introduced in 1859, the Pico Act proposed to divide California into two parts. The southern section, extending roughly from the 36th parallel southward, would have been organized as a separate territory, and the city of Los Angeles would serve as its capital. This was the city that would be placed as the seat of governance closer to the people it aimed to represent. This was not merely a geographic division; it reflected profound cultural differences between the Anglo-American settlers who had arrived during the Gold Rush and the long-established Mexican Californio communities in the south.

The California legislature passed the act and even received approval from President James Buchanan. However, for the separation to be finalized, Congress needed to endorse the proposal. At the time, the United States was already embroiled in heated debates over slavery, with sectional disputes threatening national unity. As a result, Congress never acted on the Pico Act, and California remained intact.

Significance and Legacy:

Despite never being implemented, the existence revealed the extent of dissatisfaction among the early citizens who settled in the then-new state of California. Southern communities felt neglected in terms of infrastructure, political representation, and economic opportunity. The proposal accentuated the challenge of integrating such a vast territory into a functioning state government, particularly when different regions had distinct priorities and identities.

The Pico Act also illustrates how regional tensions within California mirrored the broader divisions of the United States in the mid-19th century. Just as the nation was divided over slavery and state rights, California wrestled with its own internal divisions. While the issue of slavery was not central to the Pico Act, the cultural and political divide between the North and South of the state reflected similar dynamics of imbalance and dissatisfaction.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, the Pico Act of 1859 may not have been successful in reshaping California’s borders and organizing it in a different way; however, today it stands as a testament to the complexities that were experienced with the statehood and people’s struggle for representation on the political map. Furthermore, the act highlights the then dissatisfaction of southern Californians who wanted greater autonomy, while the state was still young and was trying to unify disparate communities. Even as an unsuccessful act, this rather small act could have impacted the organization of California as we know it today, and it will remain a window into the political climate of the time. It shall continue to serve as a reminder that California’s path to unity was neither uncontested nor straightforward, and its legacy continues to echo in conversations about regional identity and governance in America’s most populous state.